Going Deeper with Yerba Mansa

by Dara Saville

I will never forget the moment I realized that The Rio Grande Bosque and I were one in the same. Walking along on a lovely Autumn day, the scent of Yerba Mansa filled the air and the muted light brought out all the yellow pigments from Cottonwood leaves, flowering plants, and Willow thickets. The dampness of late lingering monsoons permeated the air and the glittering light of a nearby puddle caught my attention. The water was dark as coffee, covered with hovering mosquitoes, and it reflected precisely what I was feeling in that moment. My soul was filled with the Bosque.

My soul is filled with the Bosque

Since writing my first post on Yerba Mansa, I have spent much of my life in this riparian forest, home to the legendary medicinal plant. I have learned from the Cottonwood tree to nurture life and facilitate the return of Yerba Mansa and other native plants into this struggling water-deprived ecosystem. In the spirit of Cottonwood, I simply lend a little mothering help and let life unfold as it will. I began my habitat restoration work through The Yerba Mansa Project three years ago (in 2014) and it has given me unexpected gifts. I have watched newly planted Yerba Mansa patches open their first flowers and reach their stolons across the earth, rooting, leafing, and seeding new life. I have seen struggling Coyote Willow thickets rebound and many smaller native species thrive after removing the heavy competition from non-native Ravenna Grass. I have spied on toads and turtles as they go about their business in the muddy flats where I water the Yerba Mansa. When I walk in this place, I no longer dwell on what is dying. I feel what is living. In fact, I feel it invigorating me so deeply as only the spirit of Yerba Mansa can. It is the lure of a plant I have long loved, calling me into a new world within myself. It is a world of empowerment to make the changes we want to see in this world, the patience and endurance to facilitate rebirth over time, and the profound joy of being part of a living system where vitality circulates freely between me and all surrounding life.

Read more about the Bosque’s history and ecological issues here.

Bosque turtle enjoying the muddy habitat at our site

Yerba Mansa (Anemopsis californica):

As part of an annual autumn ritual, I drive to a favorite place outside of the protected urban woodlands of Rio Grande Valley State Park where the riparian wilds are less visited and still full of healthy native plants. I walk the trails in and out of forest and open spaces, along sandy beaches, through Willow thickets, and under jetty jacks. All this in search of the ancient and enduring spirit of Yerba Mansa. Yerba Mansa is considered to be a paleoherb, meaning that is among those plants close to the origin of monocotyledons3 and thus embodies the wisdom of innumerable generations. The water diversion practices in the Bosque have, however, impacted this plant. A lover of wetlands, moist soils, thick leaf litter mulch, and the shade of Cottonwood trees, it suffers from the reduction of the water table, lack of flooding, and non-native species overtaking the understory.

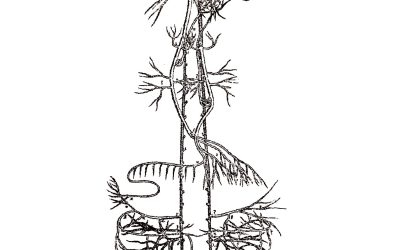

Nevertheless, large stands of Yerba Mansa still exist in some areas. Late October is the perfect time to harvest the aromatic roots of this most honored herb of the Cottonwood forests. With the seasonal song of migrating sandhill cranes in the afternoon sky and the potent scent of the roots rising from the earth, the meditation of medicine gathering begins. Crouched on the forest floor near the occupied web of a Yellow Black Garden Spider, I am reminded to enter into this landscape and the wild harvesting process with respect and awareness of the life around me. I clear away several inches of forest mulch, mainly Cottonwood leaves in varying states of decay, and begin to see individual Yerba Mansa plants within the dense stand. With my hands in the earth my work is reminiscent of a paleontological excavation as I carefully expose the horizontal rhizomes and vertical roots reaching downward for moisture. Clearing away the thick silty clay enshrouding the rhizomes is a time-consuming process with great rewards as the entirety of the treasured roots emerge. Entwined amongst thick Cottonwood roots, Yerba Mansa rhizomes display the interconnection of all beings within this forest and indeed all life everywhere as one root leads to another and the forest floor recyclers, the bugs of the Bosque, scurry away from my intrusion. The penetrating aroma of Yerba Mansa envelops me and makes us one as our vitality intermingles in the intimacy of the moment. Digging deeper, the continuum of thick rhizomes and entangled roots reveals new layers in the depths of life of this place that I love.

Yerba Mansa flowers, Anemopsis californica

Yerba Mansa is a plant of extraordinary beauty as well as an invaluable herb in the medicine cabinet. Its uniqueness is obvious at first glance and so it is not surprising to learn that Yerba Mansa is the only plant in the genus Anemopsis and one of only six plants in the family Saururaceae. Its growing habit is to create large dense stands formed both through seeding and spreading its ‘lizard tails’, or stolons, which root at each node. Its white petal-like bracts reflect a haunting iridescent glow in the desert sunset illuminating a palate of otherworldly colors. Yerba Mansa’s elegance is indeed unique amongst desert plants and has been a force holding my heart to this land for many years. As the plants move through their growing season, red splashes begin to appear on their leaves, bracts, and roots. By autumn, most of the plants are entirely deep, earthly crimson with some sheltered patches holding onto green leaves. Yerba Mansa’s transformation occurs in tandem with the entire riparian forest as fall colors emerge everywhere revealing the seasonal beauty of New Mexico’s desert valley and exposing views of the Sandia Mountain backdrop.

Autumn in the Bosque: Cottonwoods and Yerba Mansa

Enchanted by its singular beauty, I have worked with this plant lovingly for years. It is my personal medicine that finds its way into many of the formulas I make for myself. Simply experiencing the Yerba Mansa aroma sends comforting healing signals throughout my being. After harvesting, the aroma of the freshly chopped roots fills my house invigorating me every day. Indeed this plant contains several active constituents including methyleugenol (55%), thymol (13%), piperitone (5%)4, as well as sesamin5, and asarinin6, all contributing to Yerba Mansa’s many useful herbal actions within the body. It is anti-inflammatory, broadly anti-microbial, astringent, diuretic, anti-catarrhal, and tonifying to the mucous membranes with a particular affinity for the digestive, respiratory, and urinary systems. As an anti-inflammatory Yerba Mansa helps the body to excrete uric acid through diuresis and provides effective support for arthritis and other rheumatic complaints. Yerba Mansa’s antimicrobial workings are supported by research that confirms its activity against Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Geotrichim candidum7 as well as five species of mycobacterium known to cause skin, pulmonary, and lymphatic infections5. Recent research also suggests that water, alcohol, and ethyl acetate extracts of Yerba Mansa (all plant parts, but especially the roots) inhibit the growth and migration of certain types of cancer including two breast cancer cell lines, HCT-8, and colon cancer cells8, 9, 10.

Among Yerba Mansa’s most powerful attributes are its abilities to tone and tighten the mucous membranes similarly to Goldenseal and the manner in which it moves the waters and energy of the body. In its wild habitats Yerba Mansa enhances the wet boggy earth by absorbing and distributing water and adding anti-microbial and purifying elements to the damp and slow-moving ecosystem. Once a colony is established, it alters the soil chemistry and organisms, creating an environment more favorable to the growth of other plants by acidifying and aerating the soil11. It functions similarly inside the ecosystems of our bodies by regulating the flow of waters, encouraging the movement of stagnant fluids, moving toxins, and inhibiting harmful pathogens, while warming and stimulating other sluggish functions in the body. With this combination of attributes that invigorate the overall health of an organism or ecosystem, Yerba Mansa is an herb with a wide array of applications including chronic inflammatory conditions, digestive disorders, skin issues, urinary infections, mucus-producing colds and sore throats, sinus infections, hemorrhoids, oral healthcare, fungal infections, and many others.

Yerba Mansa roots

Yerba Mansa has a long history of use in the Southwest and Mexico beginning with the relationships and knowledge held by Indigenous Peoples of the region. This knowledge was taken by newly arriving Americans interested in resources that would assist colonization and published as new ‘discoveries’. Dr. W.H. George of Inyo County, California was the first eclectic physician to extol the virtues of Yerba Mansa in 1876. He and another physician Dr. Edward Palmer described its prominent, almost legendary, role in the long-standing medicine practices of Native American and Mexican people of Southern California and Sonora, Mexico. He also recognized Yerba Mansa’s stimulating effects on the mucous membranes and its effectiveness on treating nasal catarrh, rhinitis, and sore throats. He prepared a nasal spray, which he reported caused copious nasal secretions that moved the mucous and relieved the congestion12. J.A. Munk, a physician from Los Angeles, later revealed his nasal spray recipe in 1909: fill a two ounce tincture bottle with 5 to 30 drops of Yerba Mansa tincture, 1 dram of glycerin, and the rest with water12. Physician Herbert T. Webster described other common turn of the century uses of Yerba Mansa including its usefulness for bowel complaints, diarrhea, colitis, urinary issues, gonorrhea, ulcers, wounds, bruises, coughing, and consumption as well as its alterative properties12. By the middle of the twentieth century the pharmaceutical industry was beginning to undermine mainstream botanical medicine and Yerba Mansa’s use gradually retreated back to traditional herbal practices in Native American, Mexican, and Hispanic communities.

Autumn Yerba Mansa

Extracting best in alcohol and water, I like to prepare roots both as tea and tincture. Make sure your roots are from a clean location as Yerba Mansa, like most wetlands plants, is known to absorb arsenic13 and heavy metals14 from its environment. (Another good reason to be growing Yerba Mansa on farms and in backyard gardens!) While I have heard some people make the case for preparing it as an infusion, I prefer it as a decoction. The decocted roots retain their aroma nicely and impart a rich earthy flavor to the water that is unlike that of any other tea I have ever tasted. Raising the cup to my mouth, I have already received a medicinal effect before the first sip hits my tongue. To breathe in the aromatic vapors creates an automatic response; a shift in my core being that comes from the deeply soothing comfort only Mother Earth can provide. Each sip of tea spreads the restorative warmth throughout my body delivering its healing properties to the very depths of my soul.

Although not quite as fulfilling on the sensory level, the tincture is another powerful preparation that I use often. In my experience, it is best prepared using freshly dried root and 75% alcohol. Some people may like to add a small amount (up to 10%) of glycerin to prevent any precipitation in the tincture. It combines well with many other herbs for an endless variety of formulas. Ground roots are also a useful addition to herbal healing clays for wounds and to body powders for diaper rash, athlete’s foot, and the like. While the leaves have more subtle medicinal properties and can be made into infused oil for salves and creams15, I find them to be very mild compared to the roots. I use them mainly as poulticing leaves for skin inflammations and mulch in my garden. A tea prepared from leaves has also served as a traditional remedy for colic in babies and a nighttime fever reducer16.

Planting Yerba Mansa in the Bosque with the Yerba Mansa Project

Living in the Rio Grande floodplain, I am drawn regularly into my nearest wilderness, my closest refuge. As I walk between river and sky, I feel the heavy muddy silt clumping onto my hiking shoes, slowing me down; the Bosque literally grabbing on to me, filling me with awareness of the moment, and opening my senses to the spirits of the land. I see the signals of the majestic Cottonwood elders standing alone without younglings, vulnerable to the march of time. I walk many miles without the pungent sent of Yerba Mansa underfoot, replaced instead by the prickly sensations of more rugged invasive weeds. I have heard the faint whispers in my heart, the call to action. This river system and its inhabitants are not only Yerba Mansa’s habitat, they are the lifeblood of our community. The river is our past, present, and our future

Yerba Mansa and other riparian plants throughout the West are becoming increasingly vulnerable to habitat degradation as water diversion increases and rivers run dry. Advocating for water rights for ecosystems and engaging in riparian restoration projects are one of the most effective ways to protect a wide variety of native plants for the future and to safeguard the life-force critical to everyone. Clean flowing rivers and intact native plant communities create healthy bio-diverse habitat for all. The Yerba Mansa Project is helping to reestablish a healthy native plant community with increased biodiversity and improved wildlife habitat along the urbanized banks of the Rio Grande. In the process we hope not only to see more Yerba Mansa growing in our area, but also to bring its invigorating spirit into the hearts and minds of all living generations so that we may fall in love with the Bosque and come to honor and respect our most beloved wild places. The future of Yerba Mansa and other medicinal plants is still begin written and it is ours to create.

Learn More + Do More

Contribute to the Yerba Mansa Project

Read More About Yerba Mansa and the Bosque in Dara’s Monographs, Articles, and Book:

blank

Endnotes

This essay was originally published as: Saville, Dara. (2015). Yerba Mansa and the Rio Grande Bosque. Plant Healer Quarterly, 5(3), 86-93.

Endnotes:

1 US Army Corps of Engineers, Middle Rio Grande Bosque Restoration Project Final Report, July 2003.

2 Clifford S. Crawford, Lisa M. Ellis, Manuel C. Mulles Jr., “The Middle Rio Grande Bosque: An Endangered Ecosystem,” New Mexico Journal of Science 36 (1996): 276-299.

3 Sherwin Carlquist, Karen Dauer, Stefanie Y. Nishimura, “Wood and stem anatomy of Saururaceae with reference to ecology, phylogeny, and origin of the monocotyledons,” IAWA Journal 16 (1995): 133-150.

4 Ramesh N. Acharya, Madhukar G. Chaubal, :Essential oil of Anemopsis californica,” PHARM SCI 57 (1968): 1020-1022.

5 Robert O. Bussey, Arlene A. Sy-Cordero, Mario Figueroa, Frederick S. Carter, Joseph O. Falkinham, Nicholas H. Oberlies, Nadja Cech, “Antimycobacterial Furofuran Lignans from the Roots of Anemopsis californica,” Planta Medica 80 (2014): 498-501.

6 L. V. Tutupalli, M. G. Chaubal, “Constituents of Anemopsis californica,” Phytochemistry 10 (1971): 3331-3332.

7 Andrea L. Medina, Mary E. Lucero, Omar F. Holguin, Rick E. Estell, Jeff J. Posakony, Julian Simon, Mary A. O’Connell, “Composition and antimicrobial activity of Anemopsis californica leaf oil,” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 53 (2005): 8694-8698.

8 Catherine N. Kaminski, Seth L. Ferrey, Timothy Lowrey, Leo Guerra, Severine van Slambrouck, Wim F. A. Steelant, “In vitro anticancer activity of Anemopsis californica,” Oncology Letters 1 (2010): 711-715.

9 Amber L. Daniels, Severine Van Slambrouck, Robin K. Lee, Tammy S. Arguello, James Browning, Michael J. Pullin, Alexander Kornienko, Wim F. A. Steelant, “Effects of extracts from two Native American plants on proliferation of human breast and colon cancer cell lines in vitro,” Oncology Reports 15 (2006): 1327-1331.

10 Severine Van Slambrouck, Amber L. Daniels, Carla J. Hooten, Steven L. Brock, Aaron R. Jenkins, Marcia A. Ogasawara, Joann M. Baker, Glen Adkins, Eerik M. Elias, Vincent J. Agustin, Sarah R. Constantine, Michael J. Pullin, Scott T. Shors, Alexander Kornienko, Wim F. A. Steelant, “Effects of crude aqueous medicinal plant extracts on growth and invasion of breast cancer cells,” Oncology Reports 17 (2007): 1487-1492.

11 Michael Moore, Medicinal Plants of the Desert and Canyon West, (Santa Fe NM: Museum of New Mexico, 1989) 133-134.

12 Wm P. Best, “Anemopsis californica: a pleasant, non-poisonous mucous-membrane remedy,” National Eclectic Medical Association Quarterly 12 (1921): 619-629.

13 Lizette Del-Toro-Sanchez, Carmen Zurita, Florentina Gutierrez-Lomeli, Melesio Solis-Sanchez, Brenda Wence-Chavez, Laura Rodriguez-Sahagun, Araceli Castellanos-Hernandez, Osvaldo A. Vazquez-Armenta, Gabriela Siller-Lopez, “Modulation of antioxidant defense system after long term arsenic exposure in Zantedeschia aethiopica and Anemopsis californica,” Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 94 (2013): 67-72.

14 M. M. Karpiscak, L. R. Whiteaker, J. F. Artiola, K. E. Foster, “Nutrient and heavy metal uptake and storage in constructed wetland systems in Arizona,” Water Science and Technology 44 (2001): 455-462.

15 Richo Cech, Making Plant Medicine, (Williams OR: Horizon Herbs, 2000) 241-242.

16 Michael Moore, Los Remedios, (Santa Fe NM: Museum of New Mexico Press, 1990) 83.