Going Deeper with Pedicularis

by Dara Saville

P. procera forest

There is undoubtedly a deeply alluring quality to Pedicularis plants that has drawn the attention of many herbalists and plant lovers of all kinds. For some, it is simply recovery for overworked muscles or the relaxation of tension in the body that they seek. Others may be searching for the more subtle shifts and openings that such relaxation in the physical body can bring for the mind and spirit. Indeed the sheer beauty and mysterious underground workings of these varied plants are captivating for anyone acquainted with Pedicularis. Our local species have been both good medicine and tremendous sources of inspiration and learning for me over the years. Ranging from open prairies to semi-arid foothill woodlands to alpine mountain meadows, Pedicularis lures the seeker into wild and undisturbed landscapes where the gateways are wide open. It offers us a glimpse into an underground world of intricate interactions, community coordination, and a synergistic blossoming of new creation that resides both in the land and within ourselves.

Pedicularis Genus

High elevation Pedicularis meadow

The genus Pedicularis includes over 600 species, found in prairie, montane, sub-alpine, alpine, and tundra environments across the Northern Hemisphere. Of those, 40 species can be found in North America. Pedicularis prefers habitats with undisturbed soil and moderate availability of minerals and water and generally avoids habitats with extreme environmental conditions of either high stress and disturbance or nutrient dense wet areas with higher levels of above ground vegetative competition (Tesitel et. at., 2015). The genus Pedicularis was previously grouped with the Scrophulariaceae until its parasitic members were relocated to the Orobanchaceae family where it resides today. This large genus is generally characterized by varied morphological differences, particularly in the upper lip of the corolla. Genetic and biogeographical studies suggest that all Pedicularis species originated in Asia, migrating to North America when the Bering Land Bridge was open during the Miocene (14-10 myr), subsequently dispersing across North America from ancestral Rocky Mountain and Southern Cascade Range populations, and eventually reaching Europe from populations in the eastern half of the continent (Robart et al., 2015).

Pedicularis plants are fascinating ecologically and may even be considered keystone species due to their important role in facilitating biodiversity. As hemiparasitic plants, they produce underground structures called haustoria, that create a direct connection between the xylem of the host and that of the parasite (Piehl, 1963). Pedicularis and other root hemiparasites produce their own chlorophyll and can thus survive on their own, but may obtain additional resources through these root connections to other host plants. These interactions vary depending upon the species of Pedicularis and the host plants, which commonly include asters, oaks, conifers, and grasses (Ai-Rong Li, 2012) but also include a wide variety of potential hosts from at least 80 different plant species in 35 families (Piehl). The transfer of secondary resources such as water, minerals, and alkaloids from nearby plants is well-established (Schneider and Stermitz, 1990) and has larger implications for the ecosystem in which Pedicularis makes its home. Pedicularis clearly benefits from this relationship, but there is also evidence that this phenomenon has a wide reaching ripple effect. While this hemiparasitic relationship can negatively impact the growth of the host plant, it is also associated with greater plant diversity in the bioregion (Hedberg et al. 2005). Pedicularis may inhibit the growth of plants with a propensity to dominate the landscape such as Goldenrod or grasses while its pollen-rich flowers attract bees and hummingbirds to the area for increased pollination and reproduction of other important species (Hedberg et al.). In fact, other flowering plants are likely to produce more fruits and set more seeds when growing in close proximity to Pedicularis plants (Laverty, 1992). In addition to curtailing the growth of dominating host plants and promoting the biomass and reproduction of other plants, Pedicularis also contributes to species diversity by reallocating nitrogen and other nutrients to neighboring plants through decomposition (Demey et al., 2013). These combined qualities make Pedicularis an important element in ecological restoration projects (DiGiovanni et. al, 2016).

P. parryi closeup

Aside from their ecological importance, Pedicularis plants are known in herbal medicine traditions wherever they grow. Phytochemical analysis has been done primarily on Asian species but identifies a number of common constituents including iridoid glycosides, phenylpropanoid glycosides (PhGs), lignans glycosides, flavonoids, alkaloids, and other compounds (Mao-Xing Li, 2014). Employed mainly for its muscle relaxant properties, Pedicularis is typically used in formulas for general relaxation or recovery from physical injury. The synergistic effects of Pedicularis’ many constituents result in additional properties including being antitumor, hepatoprotective, anti-oxidative, protective to red blood cells, antibacterial, and cognition enhancing (Mao-Xing Li, 2014 and Gao et al., 2011). Resent research also gives implications for broader uses as a medicinal herb. Pedicularis has been shown to have antimicrobial activity against a number of pathogens including P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, S. epidermidis P. olympica, P. vulgaris, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, C. albicans, M. luteus, and others (Khodaie et al., 2012; Dulger and Ugurlu, 2005; Yuan et al., 2007). Significantly it has also demonstrated the ability to repair DNA and lower levels of glucose and other diabetic markers (Chu, 2009; Yatoo et al., 2016). Not surprisingly Pedicularis has also been used to increase endurance in athletic performance by reducing muscle fatigue (Zhu et al., 2016). This combination of traits would make Pedicularis a useful component in a wide variety of disease prevention and treatment formulas. Due to their hemiparasitic nature, Pedicularis plants may take on additional phytochemicals and healing characteristics by absorbing resources from neighboring host plants. Through this deeply-rooted connection to their ecosystem, they may become more than they could ever be on their own. This could be a drawback in the case of plants with toxic compounds such as some Senecio species that often serve as host plants (Schneider and Stermitz, 1990). Finding Pedicularis among Aspen stands however, is like harvesting two herbs in one as the Aspen subtly shifts the energy and properties of the Pedicularis increasing its anti-inflammatory pain-relieving nature. This hemiparasitic trait, however beneficial as a medicine, is also what makes them truly wild and creates challenges for cultivation.

Working with Pedicularis draws the practicing herbalist into the prairies and mountains where she can harvest and craft remedies that are born of the wild places around her. Since Pedicularis is not commonly cultivated, most of us obtain this medicine through wildcrafting in places where this plant grows abundantly. Residing at lower latitudes and middle elevations P. centranthera, P. racemosa, and P. procera are most common where I live and have therefore become my favorite allies in this genus. There are also quite a few other species (see species profiles below) that I find in abundance when I venture into the ecozones to the north. Leaves and flowers can be harvested at different times in the growing season depending on the species and location. Lower elevation P. centranthera flowers early in the spring while most others growing at higher elevations flower in mid-summer. Be sure to leave lots of flowers and avoid disturbing roots to maintain healthy wild populations. This is a lower dose herb, so you won?t need to take much. I usually tincture some fresh in the field and take the rest home for other preparations such as infused oils, salves, and smoke blends to help with injured or overworked muscles, encourage restful sleep, to release tension residing deep within the body, and also as a catalyst to encourage shifting in the depths of ourselves when we need to see things in a new light. There is, however, something more profound, almost magical, that these plants have to offer. One of the students in my program, forgetting the plant’s name, captured that sentiment when she referred to it as “that plant that sounds like a Harry Potter spell”. While this genus has a large membership, I’ll mention just a few that I encounter in my region.

Pedicularis groenlandica:

P. groenlandica

P. groenlandica has fern-like leaves and magnificent flowering racemes with elephant-shaped flowers, giving it the common name of ‘Elephant Head Betony’. To discover an alpine meadow blanketed by P. groenlandica is like falling in love. As my eyes met this magenta mountain meadow, my first reaction was to dive in head-first, to literally fling myself into it whole-heartedly. I felt a compelling attraction profoundly pulling me into the landscape, like two souls split part and now reunited. Knowing that this plant favors boggy places, I thought better of it and instead gazed drop-jawed at the majestic beauty, walked carefully amongst the little plants, and found a place to sit and soak it all in. I knew that later I would be making deep body healing salve born directly from the landscape, but for now P. groenlandica was nourishing me in the most intangible ways. I will never forget the happiness I felt from head to toe as I laid eyes on this striking scene. Simply knowing that such places exist in the world is comforting medicine for me. P. groenlandica’s mesmerizing inflorescence heals both directly as absorbed by the body and also indirectly as absorbed by the heart. Thriving in open wetter places with a tendency towards stagnancy, think of this species when the release of muscular tension is needed to promote more movement in the musculature, heart, and mind. This plant will help us to let go and move on from problems that may be holding us back.

Pedicularis racemosa:

P. racemosa closeup

Also known as ‘Parrot Beak’, P. racemosa flowers have a unique formation resembling a white bird’s beak along with serrated lanceolate leaves, thereby differentiating it from other members of the genus described here. This plant inhabits the forest edges acting as liaison between worlds, an intermediary between light and dark. Approaching this plant, I feel it beckoning me to come deeper into the forest in search of fulfillment that only the wilderness beyond can provide. Just as its parasitic roots spread underground subtly shifting the energy of the forest ecosystem, it infiltrates the heart and implants trust and faith where fear, distrust, or other difficult emotions may reside. Working with it as plant medicine provides more than relief from musculo-skeletal aggravations; it also helps us to bridge the disparities in our own lives by connecting us with lost parts of ourselves. It summons from our own depths, the aspects of our being that we have ignored and helps us to be more complete individuals and more holistic practitioners. P. racemosa ultimately invites us to discover the unexplored magic within ourselves.

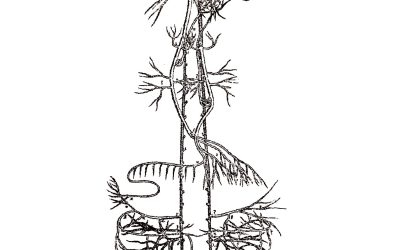

Pedicularis procera:

P. procera closeup

P. procera, or Fern Leaf Betony, is the giant of the family with large red stems and subtly striped pinkish flowers and has a way of making itself noticed in a densely populated forest environment. In fact, it stands out so much that I have seen its intricate beauty beaming forth from its towering stalks far off in the distance. I have heard it calling me off the beaten path inviting me to make my own way in the world and to discover all that the forest has to offer. Its large fern-like leaves contribute to a lush green environment relished by the desert herbalist. While all the members of this genus have a special place in my heart, this species is a treasure to work with due to the size of each plant. It is a favorite for remedies that relax the muscles, and alleviate pain, allowing us to accept ourselves as we are, and let go of what we need to shed. As a semi-parasitic plant P. procera, like other member of this genus, shares traits from nearby plants incorporating itself into the roots of the forest as well as the depths of the human body habitat when used as medicine. Of all the species discussed here, this one is the most likely to be consumed by browsing animals, who also benefit from Pedicularis re-allocating forest medicine. P. procera extends the community’s connections to an even wider circle, perhaps making it the most accessible of all species.

Pedicularis centranthera:

P. centranthera in rocky gravel

A small member of the genus that dons white flowers with spectacular magenta tips and small fern-like leaves, P. centranthera is mighty in its workings. This species prefers the semi-arid lower elevation pine and oak forests in my area and is usually seen growing in pine needle mulch. Capitalizing on early spring moisture from snow cover and melting runoff, it is one of the first plants to flower in this ecosystem every year. It is further adapted to these warmer drier elevations with its ability to shed its above ground parts, retreat back into its roots, and disappear during the hottest months of summer. Once a favorite species to harvest in my nearby wilds, I have seen its populations reduced locally due in part to environmental disturbances from land management decisions designed to reduce wildfire threats (forest thinning with masticators that destroy the understory) but also due to overharvesting in easily accessible areas. Consequently I have in recent years shifted my work toward the more abundant species found in the Southern Rocky Mountains to the north. This illustrates the concerns that many of us have for medicinal plants that are not cultivated, allowing for sustainable harvest and wide scale use in herbal medicine. My relationship with this plant also demonstrates how we can receive the medicine of plants without harvesting anything physical or tangible. P. centranthera has been an important teacher and source of strength and inspiration in my life. Through the time spent learning about this plant and yielding to its influence, I have learned much about the role of being a community coordinator; someone who brings together all the individual assets of a community and puts them to use for the benefit of the entire system. P. centranthera has shown me how to organize my community by bringing together the talents and passions of the people where I live to manifest the changes we want to see in our world and to improve the lives of everyone. Furthermore, this plant has also shown me the strategy of retreating periodically to rest and restore oneself so that we will be ready when the seasonal burst begins anew.

Pedicularis parryi:

P. parryi plants

In a moment of pure euphoria, I first discovered this plant as I crested a hill on an alpine meadow and looked out across a field of flowering P. parryi and companions. The cacophonous riot of shapes, colors, and textures of the varied flowering plants in this place seemed to shout out a chorus of thanks for the day and stood as a testament to the biodiversity-facilitating powers of Pedicularis. This plant’s flowers are similar to P. racemosa’s creamy white bird beak corolla, but with fern-like leaves typical of most other species that I know. Instead of racemosa’s forested environment, however, parryi grows in open high altitude meadows, shining light on issues we may be holding onto but do not have the clarity to understand or process. P. parryi is more direct in its workings than the other forest species and may be best suited to those of us with more concrete ways of perceiving the world and less able to shift ourselves with the more subtle workings of other Pedicularis species.

Pedicularis bracteosa:

P. bracteosa flowers

P. bracteosa is similar to procera in its lip shape, larger stature, and preference for forested habitats but its flowers are creamy white to light yellow instead of the often striped light pink to peach tones of procera. I first met this plant growing in close proximity to P. racemosa on the edge of a very dark and wild looking forest inhabited by Saxifrages, Orchids, and other sensitive plants known to favor undisturbed environments. At once I could feel the synergistic effect of these plants working together to create an ambiance of wild flowing vitality and an entrancing mood of introspection that beckoned me inward; into the forest and into myself. It was almost as if the underground haustoria were penetrating me, drawing me into the vibrational and energetic world of life in this forest, making me one with this landscape, taking me back to the source of knowledge and reconnecting with the continuum of life. It seemed in that moment as if all answers could be found right there in that forest and indeed, many were.

Pedicularis’ infiltrating personality, ecological importance, and medicinal magic have given it a beloved place in many herbalists’ hearts. This plant’s most profound activity occurs where no one can see, as its’ workings take place underneath the surface of the earth and in the depths of ourselves, releasing us from where we are stuck in our bodies, in our minds, and our hearts. In addition to its well-known muscle relaxant qualities, resent research also suggests a wider role in the prevention and treatment of diseases including diabetes and varied microbial infections. Pedicualris and other hemiparasitic plants can significantly change plant communities by fostering species diversity and floral quality in native plants as it coordinates the collective resources of the community and allocates them for the benefit of the entire system. Although this plant is not endangered in the Western United States, we must be certain to harvest with knowledge about each species’ ecological status and respect for local native plant communities. Pedicularis is not cultivated and increased demand for this herb could cause concern for wild populations, especially those that are more easily accessible. As you wildcraft this plant, take time to identify the species and observe the size, health, and frequency of populations you find. Working with Pedicularis is certain to draw you into new territory within yourself and within your practice. Pedicularis is both medicine and teacher, willing to guide us wherever we are to go.

This essay originally appeared in Plant Healer‘s Good Medicine Confluence Class Essays for 2017.

blank

References

Ai-Rong Li, F. Andrew Smith , Sally E. Smith, Kai-Yun Guan, “Two sympatric root hemiparasitic Pedicularis species differ in host dependency and selectivity under phosphorus limitation,” Functional Plant Biology 39 (9) (2012): 784-794.

Andreas Demey, Els Ameloot, Jeroen Staelens, An De Schrijver, Gorik Verstraeten, Pascal Boeckx, Martin Hermy, Kris Verheyen, “Effects of two contrasting hemiparisitic plant species on biomass production and nitrogen availability,” Oecologia 173: 1 (2013): 293- 303.

Andrew M. Hedberg, Victoria A. Borowicz, Joseph E. Armstrong, “Interactions between a hemiparasitic plant, Pedicularis canadensis L. (Orobanchaceae), and members of a tallgrass prairie community,” The Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 132: 3 (2005): 401-410.

B. Dulger, E. Ugurlu, “Evaluation of antimicrobial activity of some endemic Scrophulariaceae members from Turkey,” Pharmaceutical Biology 43:3 (2005): 275-279.

Bruce W. Robart, Carl Gladys, Tom Frank, Stephen Kilpatrick. “Phylogeny and Biogeography of North American and Asian Pedicularis,” Systematic Botany 40: 1 (2015): 229-258.

C. S. Yuan, X. B. Sun, P. H. Zhao, M. A. Cao, “Antibacterial constituents from Pedicularis armata,” Journal of Asian Natural Products Research 9:7 (2007): 673-677.

Hongbiao Chi, Ninghua Tan, Caisheng Peng, “Progress in research on Pedicularis plants,” China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica 34: 19 (2009): 2536-46.

Jakub Titel, Pavel Fibich, Francesco de Bello, Milan Chytry, Jan Lep ,”Habitats and ecological niches of root-hemiparasitic plants: an assessment based on a large database of vegetation plots,” Preslia 87(2015): 87?108.

Jane P. DiGiovanni, William P. Wysocki, Sean V. Burke, Melvin R. Duvall, Nicholas A. Barber, “The role of hemiparasitic plants: influencing tallgrass prairie quality, diversity, and structure,” Restoration Ecology doi:10.1111/rec.12446 (2016).

Laleh Khodaie, Abbas Delazar, Farzane Lotfipour, Hossein Nazemiyeh, Solmaz Asnaashari, Sedighe B. Moghadam, Lutfun Nahar, Satyajit D. Sarker, “Phytochemistry and bioactivity of Pedicularis sibthorpii growing in Iran,” Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia 22:?6?(2012): 1268-1275.

M. A. Piehl, “Mode of attachment, haustorium structure, and hosts of Pedicularis canadensi,” American Journal of Botany 50: 10 (1963): 978-985.

Mao-Xing Li, Xi-Rui He, Rui Tao, Xinyuan Cao. “Phytochemistry and Pharmacology of the Genus Pedicularis Used in Traditional Chinese Medicine,” American Journal of Chinese Medicine 42 (2014): 1071.

Marilyn J. Schneider, Frank R. Stermitz, “Uptake of host plant alkaloids by root parasitic Pedicularis species,” Phytochemistry 29 (6) (1990): 1811?1814.

T.M. Laverty, “Plant interactions for pollinator visits: a test of the magnet species effect,” Oecologia 89: 4 (1992): 502-508.

Meiju Zhua, Hongzhu Zhua, Ninghua Tanb, Hui Wanga, Hongbiao Chua, Chonglin Zhanga, “Central anti-fatigue activity of verbascoside,” Neuroscience Letters 616 (2016): 75-79.

Meili Gao, Yongfei Li, Jianxiong Yang, “Protective effect of Pedicularis decora Franch root extracts on oxidative stress and hepatic injury in alloxan-induced diabetic mice,” Journal of Medicinal Plants Research 5:24 (October 2011): 5848-5856.

Mohd. Iqbal Yatoo, Umesh Dimri, Arumugam Gopalakrishan, Mani Saminathan, Kuldeep Dhama, Karikalan Mathesh, Archana Saxena, Devi Gopinath and Shahid Husain, “Antidiabetic and Oxidative Stress Ameliorative Potential of Ethanolic Extract of Pedicularis longiflora,” International Journal of Pharmacology 12:3 (2016): 177.