Old World Herbs in the American West

by Dara Saville

Around the globe plants and people have been making relationships since the early days of humanity. Five thousand year old clay tablets from Sumeria, ancient Chinese texts, and an Egyptian papyrus from the second millennium BCE collectively describe over 1,000 medicinal herbs. There is ample evidence of Neanderthal use of medicinal herbs for pain relief, antibiotics, wild food seasonings, and ritual burials in archaeological finds dating back more than 50,000 years. Even today more than half of all modern drugs are created from plants. In Old World Europe, where much of our current American herbal apothecary originates, relationships with plants stem from a long continuum of historical and cultural traditions that were much closer to the natural world than ours. Old World relationships with herbs include a legacy embracing supernatural magic, astrology, and the personalities of plants in everyday life. While the American herbal tradition is pieced together from a multitude of herbal lineages, many traditions have been fragmented and its strongest and most accessible influences often emerge from a relatively recent culture of dominating nature. Stirring up nostalgia for a simpler way of life and creating a vision for a healthy and vibrant future, the recent popularity of medicinal plants represents for many an escape from our over-consumerist existence while providing a window into our shared past. Wildflowers have the ability to serve as a source of inspiration and contemplation, a metaphor for understanding the natural world and our own ephemeral nature while simultaneously representing the endurance of life. Despite differences, connecting the Old World and New World herbal traditions is not a far reach, as many of these plants migrated with people to occupy gardens or naturalize in new areas while others have close biological relatives across the ocean. For many of us, these plants represent a continuum of our shared ancestry. The three herbal shorts that follow describe some of the historical and cultural background of Saint John’s Wort, Vervain, and Yarrow that shapes our views and uses of these plants today and also allows us to share a snippet of our ancestors’ experience.

Imagine brightly colored garlands of white Yarrow, golden Saint John’s Wort, and purple sprigs of Vervain hanging over doorways, decorating our homes and businesses. These plants once had a much broader role in the lives of people beyond serving as food and medicine. In Medieval Europe, they were not merely beautiful and fragrant decor but vital personalities integrated into daily life for the purposes of healing, protection, and magic. They were seen as living entities with their own character and powers beyond what can be observed with the usual senses or quantified by any measurements. Celebrations, festivities, and ceremonies dotted the calendar year and provided numerous openings for plants to move into the center of sacred rituals that bound societies together. Verbenalia, a special day of alter decorating in Ancient Rome, was named for the sacred plant Verbena. Likewise, Saint John’s Feast Day, celebrated since the fourth century CE by Europeans, featured the protective powers of bonfires topped with flaming Saint John’s Wort. Plants featured in so many aspects of life by lifting the spirit in celebration and giving people the strength and empowerment they needed to face the fears of their time. Whether is was Saint John’s Wort for witchcraft in the Dark Ages or Vervain for modern day political burnout, plants have long been companions and symbols of health, protection, and resilience. As native residents of multiple continents and healing herbs in varied and geographically widespread cultures, Yarrow, Saint John’s Wort, and Vervain are among the plants that create an herbal continuum across time and space. When we explore their history they can even pull back the curtain, revealing the cultural and biological world known to our ancestors.

Saint John’s Wort

Old World: Hypericum perforatum

New World: Hypericum scouleri, H. spp

Saint John’s Wort is a plant with an ancient history of use in medicine and ceremony. Famous for its wound healing powers and affecting the supernatural realm, it was a preferred wound care herb for returning knights from the Crusades and a defense against evil and black magic, going back at least to the Middle Ages. It was customary to pick flowers on June 24, the eve of Saint John’s Feast Day, for floral garlands that were strung together with Vervain and Yarrow. These were hung over doorways to prevent the passage of harmful spirits or spells. Bonfires were topped with cuttings of Saint John’s Wort and set alight to disrupt dark and deadly forces during especially perilous times of year that were marked by increased supernatural activity. The protective powers of this herb were so potent that it was also referred to as fuga daemonium, ‘devil’s flight’. It was commonly thought that the devil hated the plant so much he stabbed the leaves repeatedly with a dagger causing all the tiny red dots to appear on August 29, the day of Saint John’s beheading. The blood of the Saint increased the plant’s protective powers. This story explains the botanical name Hypericum, meaning ‘over an apparition’ or ‘over an icon’ and perforatum, ‘tiny leaf punctures’. The protective magic and lore of Saint John’s Wort are related to this plant’s medicinal uses. During the Middle Ages, psychiatric problems were often perceived and described as effects of evil and witchcraft, thus it is no surprise that Saint John’s Wort has long been used in combination with other herbs for the treatment of a variety of mood and mental health conditions. As a symbol for healing, it became the flower emblem for the Saint John Ambulance Brigade founded in 1877 and the potency of the herb was even recognized by King George VI, who named one of his racehorses Hypericum. The popularity of Saint John’s Wort endures and it has become one of the most widely researched and studied herbal medicines of the modern era.

Saint John’s Wort is a plant with an ancient history of use in medicine and ceremony. Famous for its wound healing powers and affecting the supernatural realm, it was a preferred wound care herb for returning knights from the Crusades and a defense against evil and black magic, going back at least to the Middle Ages. It was customary to pick flowers on June 24, the eve of Saint John’s Feast Day, for floral garlands that were strung together with Vervain and Yarrow. These were hung over doorways to prevent the passage of harmful spirits or spells. Bonfires were topped with cuttings of Saint John’s Wort and set alight to disrupt dark and deadly forces during especially perilous times of year that were marked by increased supernatural activity. The protective powers of this herb were so potent that it was also referred to as fuga daemonium, ‘devil’s flight’. It was commonly thought that the devil hated the plant so much he stabbed the leaves repeatedly with a dagger causing all the tiny red dots to appear on August 29, the day of Saint John’s beheading. The blood of the Saint increased the plant’s protective powers. This story explains the botanical name Hypericum, meaning ‘over an apparition’ or ‘over an icon’ and perforatum, ‘tiny leaf punctures’. The protective magic and lore of Saint John’s Wort are related to this plant’s medicinal uses. During the Middle Ages, psychiatric problems were often perceived and described as effects of evil and witchcraft, thus it is no surprise that Saint John’s Wort has long been used in combination with other herbs for the treatment of a variety of mood and mental health conditions. As a symbol for healing, it became the flower emblem for the Saint John Ambulance Brigade founded in 1877 and the potency of the herb was even recognized by King George VI, who named one of his racehorses Hypericum. The popularity of Saint John’s Wort endures and it has become one of the most widely researched and studied herbal medicines of the modern era.

Vervain

Old World: Verbena officinalis

New World: Verbena hastata, V. macdougalii, V. spp

Vervain is one of the most highly esteemed of the Old World herbs due, in part, to its strong association with sacred and magical properties. Its protective symbolism and ability to evoke a sense of well-being resulted in long-standing and widely practiced traditions such as the sprinkling of Vervain infused water around a gathering to clear negative or harmful influences and invigorate the guests. Stretching across Mesopotamian, Greek, Roman, Middle Age, Druid, and modern cultures this herb was placed on altars, woven into crowns, used to evoke enchantments, protect against evil, and heal a variety of ailments. In ancient Greece Vervain was associated with Gods as it purified Zeus’ table before celebrations and was woven into Aphrodite’s crown. This plant’s use in love charms continued well into Medieval times and its aphrodisiac effects were considered to be so potent that it could re-conjure lost love and convert enemies. The Romans also placed high value on Vervain as a sacred purifying plant and used it in ceremonies and celebrations including the altar-decorating festival of Verbenalia. Messengers, heralds, and ambassadors all wore Vervain as a badge of office and military leaders wore it for protection in battle. During the Middle Ages, this powerful herb was used in practices of dark magic and witchcraft, but also as an antidote to those forces by hanging it along doorways with Saint John’s Wort and Yarrow for protection against such malevolent influences. Among the Welsh Vervain was known as ‘Devil’s Bane’ and was dipped into holy water to be used around church buildings and cemeteries safeguarding these places and also prepared it as incense for exorcisms. Druids were also known to use Vervain in ceremonies and left offerings before harvesting. According to Christian texts this sacred herb was even present at Christ’s crucifixion and used to heal his wounds. Vervain continues to be used for a variety of herbal applications but one of its oft forgotten uses is for treating edema and clearing urinary stones though diuresis. This once prominent use may be the origin of the name Vervain, from the Celtic ferfain, meaning to drive away (fer) a stone (faen). Few other plants share such a revered and enduring place in herbal lore.

Vervain is one of the most highly esteemed of the Old World herbs due, in part, to its strong association with sacred and magical properties. Its protective symbolism and ability to evoke a sense of well-being resulted in long-standing and widely practiced traditions such as the sprinkling of Vervain infused water around a gathering to clear negative or harmful influences and invigorate the guests. Stretching across Mesopotamian, Greek, Roman, Middle Age, Druid, and modern cultures this herb was placed on altars, woven into crowns, used to evoke enchantments, protect against evil, and heal a variety of ailments. In ancient Greece Vervain was associated with Gods as it purified Zeus’ table before celebrations and was woven into Aphrodite’s crown. This plant’s use in love charms continued well into Medieval times and its aphrodisiac effects were considered to be so potent that it could re-conjure lost love and convert enemies. The Romans also placed high value on Vervain as a sacred purifying plant and used it in ceremonies and celebrations including the altar-decorating festival of Verbenalia. Messengers, heralds, and ambassadors all wore Vervain as a badge of office and military leaders wore it for protection in battle. During the Middle Ages, this powerful herb was used in practices of dark magic and witchcraft, but also as an antidote to those forces by hanging it along doorways with Saint John’s Wort and Yarrow for protection against such malevolent influences. Among the Welsh Vervain was known as ‘Devil’s Bane’ and was dipped into holy water to be used around church buildings and cemeteries safeguarding these places and also prepared it as incense for exorcisms. Druids were also known to use Vervain in ceremonies and left offerings before harvesting. According to Christian texts this sacred herb was even present at Christ’s crucifixion and used to heal his wounds. Vervain continues to be used for a variety of herbal applications but one of its oft forgotten uses is for treating edema and clearing urinary stones though diuresis. This once prominent use may be the origin of the name Vervain, from the Celtic ferfain, meaning to drive away (fer) a stone (faen). Few other plants share such a revered and enduring place in herbal lore.

Yarrow

Old World: Achillea millefolium

New World: Achillea millefolium

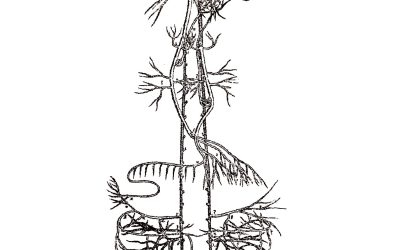

Yarrow is one of the most famous of all medicinal plants and finds a place in herbal traditions around the world. It is an herb of mythical stories and a central plant of ritual, ceremony, and healing. Native to both the Old World and the New, it is common across continents and is one of world’s oldest known herbal remedies. Found in a 65,000 year-old Neanderthal grave in Iraq, Yarrow’s medicinal and ceremonial history is one of humanity’s oldest stories of the connections between plants and people. The legend of Yarrow continues into the ancient world at the Siege of Troy around 1250 B.C.E., where its healing powers were employed. Following the advice of his famed teacher and great healer, the centaur Chiron, the warrior Achilles is said to have treated the wounds of his ally Telemachus using the herb Yarrow. This story not only illuminates Yarrow’s long-standing medicinal importance but it also helps to explain its botanical name, Achillea, along with its leaves of thousands (millefolium) of dissections. Hundreds of years after Troy, Yarrow was one of the plant remedies carried aboard a Roman ship dated between 140-120 B.C.E. and its medicinal properties were later recorded by Pliny the Elder and Dioscorides in the first century C.E. Along with Saint John’s Wort and Vervain, Yarrow was a primary herb of protection against evil spirits in Medieval times and was hung as a defender of health and safety. Today Yarrow remains one of our most widely used apothecary herbs across geographically and culturally diverse healing practices.

Yarrow is one of the most famous of all medicinal plants and finds a place in herbal traditions around the world. It is an herb of mythical stories and a central plant of ritual, ceremony, and healing. Native to both the Old World and the New, it is common across continents and is one of world’s oldest known herbal remedies. Found in a 65,000 year-old Neanderthal grave in Iraq, Yarrow’s medicinal and ceremonial history is one of humanity’s oldest stories of the connections between plants and people. The legend of Yarrow continues into the ancient world at the Siege of Troy around 1250 B.C.E., where its healing powers were employed. Following the advice of his famed teacher and great healer, the centaur Chiron, the warrior Achilles is said to have treated the wounds of his ally Telemachus using the herb Yarrow. This story not only illuminates Yarrow’s long-standing medicinal importance but it also helps to explain its botanical name, Achillea, along with its leaves of thousands (millefolium) of dissections. Hundreds of years after Troy, Yarrow was one of the plant remedies carried aboard a Roman ship dated between 140-120 B.C.E. and its medicinal properties were later recorded by Pliny the Elder and Dioscorides in the first century C.E. Along with Saint John’s Wort and Vervain, Yarrow was a primary herb of protection against evil spirits in Medieval times and was hung as a defender of health and safety. Today Yarrow remains one of our most widely used apothecary herbs across geographically and culturally diverse healing practices.

These three plants along with numerous others represent links in the herbal continuum of the people and plants in the Old World and New World. While some parts of the traditions have been left behind, others remain as the connectors between worlds and serve as bridges to our ancestors. Plants may symbolize many things in our lives from nourishment to beauty to healing to ecological functioning but their ability to unite us with our own lineages and to each other takes on new importance in the modern era when fractures and divisions seem larger than ever. During a recent journey to the Old World where my ancestors once walked the land, I felt this deep connection offered by familiar plants not only to my family but to all of humanity. Let us immerse ourselves in the oneness that plants put forth and soak in our commonality.

This essay was adapted from the original publication: Saville, Dara. “Herbal Tales Connecting the Old World and the American West, Part II.” Plant Healer 4, no. 2 (2019): 78-87.

References:

Applequist, Wendy, and Daniel Moerman. “Yarrow (Achillea millefoilum): A Neglected Panacea? A Review of Ethnobotany, Bioactivity, and Biomedical Research.” Economic Botany 65, no. 2 (2011): 209?225.

Culpeper, Nicolas. Culpeper’s Complete Herbal. London: Arcturus, 2018. (Originally published in 1653.)

Grieve, Maude. A Modern Herbal. New York: Dover Publications, 1971. (Original publication 1931, Harcourt, Brace, & Company.)

Leroi-Gourhan, Arlette. “The Flowers Found with Shanidar IV, a Neanderthal Burial in Iraq.” Science 190, no. 4214 (October 1975): 562-564.

Richardson, Rosamond. Britain’s Wild Flowers. London: National Trust, 2017.

Solecki, Ralph S. “Shanidar IV, a Neanderthal Flower Burial in Northern Iraq.” Science 190, no. 4217 (November 1975): 880-881.